|

|

| CHAPTER 5: UNIFORM FLOW |

5.1 UNIFORM FLOW

|

|

Uniform flow is strictly applicable only to a prismatic channel.

In uniform flow, flow depth, flow area, mean velocity, and discharge are constant along the channel.

For nonprismatic (natural) channels of nearly uniform cross section, the term equilibrium flow is often used to describe the flow condition that approximates or resembles the uniform flow of prismatic channels.

In uniform flow, all slopes, friction slope Sf, energy slope Se, water-surface slope Sw, and bottom slope So, are constant and equal to one slope: S.

Sf = Se = Sw = So = S

| (5-1) |

There is no such thing as unsteady uniform flow. If the flow is unsteady, it is simply not uniform.

However, under a Vedernikov number V = 1, uniform flow becomes neutrally stable and this is conducive to the development of roll waves (Section 1.3).

This is the "instability of uniform flow" described by Chow (1959). At V < 1, flow disturbances are attenuated, and roll waves do not develop.

Establishment of uniform flow

From a mechanical standpoint, uniform flow occurs in a control volume when the frictional force is equal to the gravitational force.

In the absence of section controls (Section 4.3), all open-channel flows tend toward uniform flow.

In essence, Mother Nature "likes uniform flow."

In uniform flow, the property of uniqueness of the discharge-flow area rating (or discharge-flow depth rating) qualifies uniform flow as a channel control.

Thus, uniform critical flow is a very strong type of open-channel control.

The depth of uniform flow is referred to as normal depth.

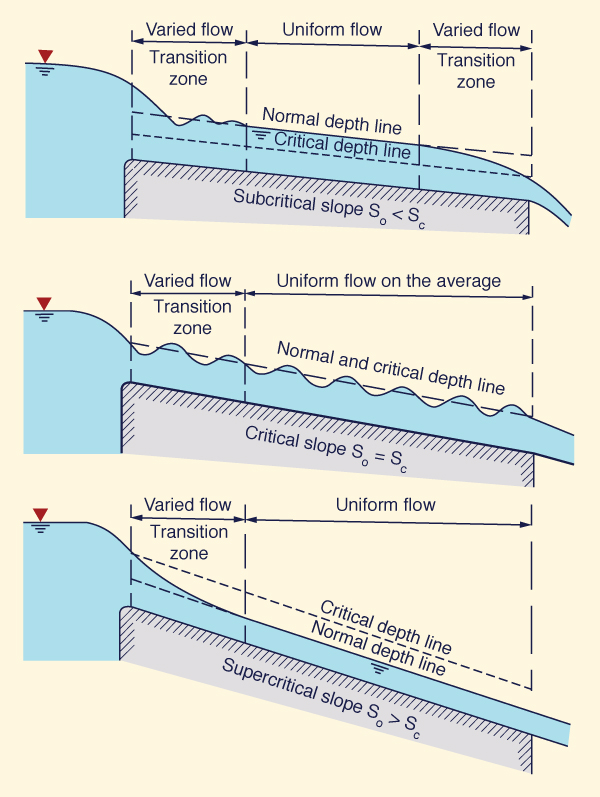

Figure 5-1 shows the establishment of uniform flow in a sufficiently long channel.

The top figure depicts subcritical normal flow, with upstream and downstream section controls.

The center figure depicts critical flow, with upstream and downstream section controls.

The bottom figure depicts supercritical normal flow, with upstream section control only.

|

Velocity of uniform flow

In general, the mean velocity of uniform flow is described by the following formula:

| V = C R x S y | (5-2) |

in which C = friction coefficient, R = hydraulic radius, defined as R = A/P, and x and y are exponents of R and S, respectively.

The exponents vary with type of roughness (laminar, turbulent, transitional, or mixed laminar-turbulent) and cross-sectional shape (arbitrary, hydraulically wide, rectangular, trapezoidal, triangular, or inherently stable).

In practice, there are two established uniform flow formulas: (1) the Chézy formula, and (2) the Manning formula.

Variations of these formulas are in current use (the dimensionless Chézy and the Manning-Strickler).

5.2 CHÉZY FORMULA

|

|

To derive the Chézy formula, the shear stress τb developed along the channel bottom is modeled as a quadratic friction law:

| τb = ρ f V 2 | (5-3) |

in which ρ = mass density, f = a type of friction factor (drag coefficient), and V = mean velocity.

This equation is dimensionless; therefore, it has a strong theoretical basis.

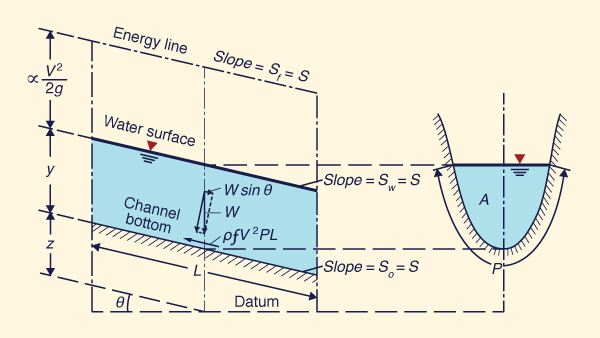

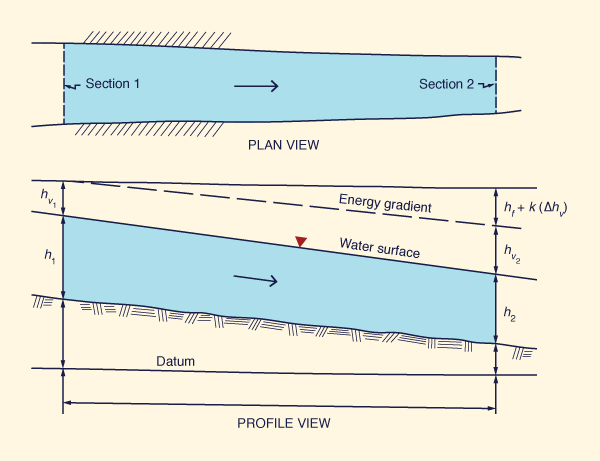

The shear force developed along the wetted perimeter of a control volume of length L is (Fig. 5-2):

| Fs = τb PL = ρ f V 2 PL | (5-4) |

|

The weight of the water in the control volume is W.

This gravitational force is resolved along the direction of motion to give:

| Fg = W sin θ | (5-5) |

For a channel of small slope: sin θ ≅ tan θ = S. Therefore:

| Fg = W tan θ = W S = γ A L S | (5-6) |

Equating frictional (Eq. 5-4) and gravitational forces (Eq. 5-6):

| ρ f V 2 P = γ A S | (5-7) |

which reduces to:

| f V 2 = g (A /P ) S = g R S | (5-8) |

where R = hydraulic radius.

Solving for V:

| V = (g/f )1/2 (R S ) 1/2 | (5-9) |

| V = C (R S )1/2 | (5-10) |

in which C = Chézy coefficient, defined as follows:

| C = (g/f )1/2 | (5-11) |

Thus, the friction factor f in Eq. 5-3 is:

| g f = ______ C 2 | (5-12) |

Equation 5-10 is the Chézy formula.

A variation of the Chézy formula may be derived by solving for bottom slope S from Eq. 5-8:

|

V 2 S = f _____ g R | (5-13) |

which is equivalent to:

|

D V 2 S = f _____ _____ R g D | (5-14) |

Given Eq. 4-6, Eq. 5-14 reduces to:

|

D S = f _____ F 2 R | (5-15) |

Equation 5-15 is basically the same as Eq. 4-5, which was derived from the Darcy-Weisbach equation applied to open-channel flow.

Thus, the dimensionless Chézy equation (Eq. 5-15) and the modified Darcy-Weisbach equation (Eq. 4-5) are the same.

For a hydraulically wide channel, D ≅ R, and Eq. 5-15 reduces to:

|

S = f F 2 | (5-16) |

which is the same as Eq. 4-8.

Table 5-1 shows corresponding values of f, Darcy-Weisbach friction factor f, and Chézy coefficients.

| [See also Lab video: Establishment of uniform flow]. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||

|

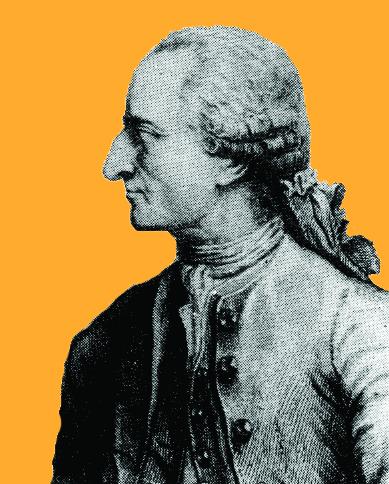

Antoine Chézy was born at Chalon-sur-Marne, France, on September 1, 1718, and died on October 4, 1798. In 1749, working in Amsterdam, Cornelius Velsen stated:

"The velocity should be proportional to the square root of the slope." In 1757, in Hannover, Germany, Albert Brahms wrote:

"The decelerative action of the bed in uniform flow was not only equal to the accelerative action of gravity but also proportional to the square of the velocity." Velsen and Brahms were working on the general laws and theories of Torricelli and Bernoulli. Chézy used some of these ideas to develop his formula. Chézy was given the task to determine the cross section and the related discharge for a proposed canal on the river Yvette, which is close to Paris, but at a higher elevation. Since 1769, he was collecting experimental data from the canal of Courpalet and from the river Seine. His studies and conclusions are contained in a report to Mr. Perronet dated October 21, 1775. The original document, written in French, is titled "Thesis on the velocity of the flow in a given ditch," and it is signed by Mr. Chézy, General Inspector of des Ponts et Chaussées. It resides in file No. 847, Ms. 1915 of the collection of manuscripts in the library of the École. In 1776, Chézy wrote another paper, entitled: "Formula to find the uniform velocity that the water will have in a ditch or in a canal of which the slope is known." This document resides in the same file [No. 847, Ms. 1915]. It contains the famous Chézy formula: V = 272 (ah/p)1/2 in which h is the slope, a is the area, and p is the wetted perimeter. The coefficient 272 is given for the canal of Courpalet in an old system of units. In the metric system, the equivalent value is: V = 31 (ah/p)1/2 For the river Seine, the value of the coefficient is 44. Clemens translated into English the two Chézy papers. Riche de Prony, one of Chézy's former students, was the first to use the Chézy formula. Later, in 1801, in Germany, Eytelwein used Chézy's and De Prony's ideas to further the development of the formula. |

5.3 MANNING FORMULA

|

|

The Manning formula, in SI units, is:

| 1 V = ____ R 2/3 S 1/2 n | (5-17) |

where n = Manning's friction coefficient, friction factor, or simply Manning's n.

In U.S. Customary units, the Manning formula is:

| 1.486 V = ________ R 2/3 S 1/2 n | (5-18) |

The quantity 1.486 is a conversion factor arising from the equivalence 1.486 = 1/(0.3048)1/3.

The factor is required to express the original Manning equation (Eq. 5-17) in U.S. Customary units.

In order to compare with the Chézy formula, the Manning equation is expressed as follows:

| 1.486 V = ________ R 1/6 R 1/2 S 1/2 n | (5-19) |

Comparing Eqs. 5-10 and 5-19, the relation between Manning and Chézy coefficients is obtained:

| 1.486 C = ________ R 1/6 n | (5-20) |

Equation 5-20 implies that while C varies with the hydraulic radius, the value of n does not.

This may be approximately true for (artificial) prismatic channels, but it is generally not true for natural channels (Barnes, 1967).

In natural channels, the value of n may vary with stage and flow depth.

This is attributed to:

Natural variations in channel roughness with increasing stage, including the effect of overbank flows (Fig. 2-15), or

Morphological changes in total bottom friction, composed of skin and form friction, as the flow rises from low stage, through intermediate stage, to high stage (Simons and Richardson, 1966).

Empirical formulas for Manning's n

Several correlations between Manning's n and particle size (grain diameter) have been developed.

Williamson (1951) correlated the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor f with relative roughness to yield the following relation (Henderson, 1966):

| ks f = 0.113 ( ____ ) 1/3 R | (5-21) |

in which ks = grain roughness, in length units, and R = hydraulic radius.

Since f = 8 (g /C 2), Eq. 5-21 reduces to:

| 8g R C = ( ________ )1/2 ( _____ ) 1/6 0.113 ks | (5-22) |

In U.S. Customary units, Eq. 5-22 may be conveniently reduced to:

|

1.486 R1/6 C = ________________ 0.0311 ks1/6 | (5-23) |

Comparing Eq. 5-23 with Eq. 5-20, n can be expressed in terms of boundary roughness as follows (ks in ft):

| n = 0.0311 ks1/6 | (5-24) |

A general expression for Manning's n in terms of relative roughness and absolute roughness is (Chow, 1959):

| n = [f (R/ks)] ks1/6 | (5-25) |

which implies that in Eq. 5-24 the relative roughness is a constant (0.0311).

Assuming that boundary roughness may be represented by the d84 particle size, i.e., that for which 84% of the grains (by weight) are finer, Eq. 5-24 converts to:

| n = 0.0311 d841/6 | (5-26) |

Strickler used a constant (0.0342) for the function of relative roughness f(R/ks), and the median particle size d50 as the representative grain diameter, to yield:

| n = 0.0342 d501/6 | (5-27) |

Since d84 > d50, it is seen that the Strickler and Williamson equations are mutually consistent.

Table 5-2 shows values of Manning's n calculated with the Strickler formula (Eq. 5-27).

| ||||||||||||||

| ||||

|

Robert Manning was born in Normandy, France, in 1816, and died in 1897. In 1826, he moved to Waterford, Ireland, and worked as an accountant. In 1846, during the year of the great famine, Manning was recruited into the Arterial Drainage Division of the Irish Office of Public Works. After working as a draftsman for a while, he was promoted to assistant engineer. In 1848, he became district engineer, a position he held until 1855. As a district engineer, he read "Traité d'Hydraulique" by d'Aubisson des Voissons, after which he developed a great interest in hydraulics. From 1855 to 1869, Manning was employed by the Marquis of Downshire, while he supervised the construction of the Dundrum Bay Harbor in Ireland and designed a water supply system for Belfast. After the Marquis' death in 1869, Manning returned to the Irish Office of Public Works as assistant to the chief engineer. He became chief engineer in 1874, a position he held it until his retirement in 1891. Manning did not receive any education or formal training in fluid mechanics or engineering. His accounting background and pragmatism influenced his work and drove him to reduce problems to their simplest form. He compared and evaluated seven best known formulas of the time: Du Buat (1786), Eyelwein (1814), Weisbach (1845), St. Venant (1851), Neville (1860), Darcy and Bazin (1865), and Ganguillet and Kutter (1869). He calculated the velocity obtained from each formula for a given slope and for hydraulic radius varying from 0.25 m to 30 m. Then, for each condition, he found the mean value of the seven velocities and developed a formula that best fitted the data. Manning's original best-fit formula was the following: V = 32 [RS (1 + R1/3)]1/2 which he later simplified to: V = C Rx S1/2 In 1885, Manning gave x the value of 2/3 and wrote his formula as follows: V = C R2/3 S1/2 In a letter to Flamant, Manning stated: "The reciprocal of C corresponds closely with that of n, as determined by Ganguillet and Kutter; both C and n being constant for the same channel." On December 4, 1889, at the age of 73, Manning first proposed his formula to the Institution of Civil Engineers (Ireland). This formula saw the light in 1891, in a paper written by him entitled "On the flow of water in open channels and pipes," published in the Transactions of the Institution of Civil Engineers (Ireland). Manning did not like his own equation for two reasons: First, it was difficult in those days to determine the cube root of a number and then square it to arrive at a number to the 2/3 power. In addition, the equation was dimensionally incorrect, and so to obtain dimensional correctness he developed the following equation: V = C (gS)1/2 [R1/2 + (0.22/m1/2 )(R - 0.15 m)] where m = "height of a column of mercury which balances the atmosphere," and C was a dimensionless number "which varies with the nature of the surface." However, in late 19th century textbooks, the Manning formula was written as follows:

V = (1/n) R2/3 S1/2

Through his "Handbook of Hydraulics," King (1918) led to the widespread use of the Manning formula as it is known today, as well as to the acceptance that the Manning coefficient C should be the reciprocal of Kutter's n. In the United States, n is referred to as Manning's friction factor, or simply Manning's n. In Europe, the Strickler K is the same as Manning's C, i.e., the reciprocal of n. When K is used in lieu of n, the Manning equation is referred to as the Manning-Strickler or Strickler equation. |

5.4 MANNING ROUGHNESS

|

|

Given Eq. 5-17 (or 5-18), once three of the variables are known, the fourth one can be calculated.

Typically, R and S are known, and n is estimated, from which V can be calculated.

This is the direct method, the most typical way of using the Manning equation.

When increased accuracy is required, or else, when n cannot be estimated with complete certainty, a measurement of velocity V, together with the measurement of hydraulic radius R and channel slope S, is recommended to calculate n.

This procedure is referred to as the inverse method, or the calibration method.

In practice, most applications have used the direct method.

Estimation of Manning's n

There is no exact method or procedure to estimate Manning's n.

A proven set of recommendations is given below.

Recommendations for the estimation of Manning's n

|

Chow (1959) presented a pictorial collection of twenty-four (24) typical channels for which the Manning's n has been established.

The values documented by Chow range from n = 0.012 (a canal lined with concrete slabs, with very smooth surface) to n = 0.150 (a natural river in sand clay soil, irregular sides slopes and uneven bottom).

Chow (1959) listed values of Manning's coefficient as low as n = 0.008 (lucite, acryclic plastic) to as high as n = 0.200 (flood plains of natural streams, with dense willows, in the summer) (Table 5-4).

These values are applicable to channel flow in the turbulent regime.

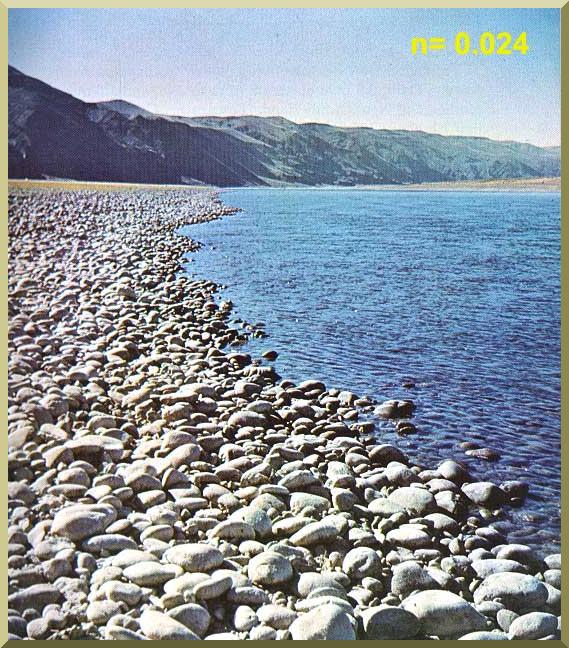

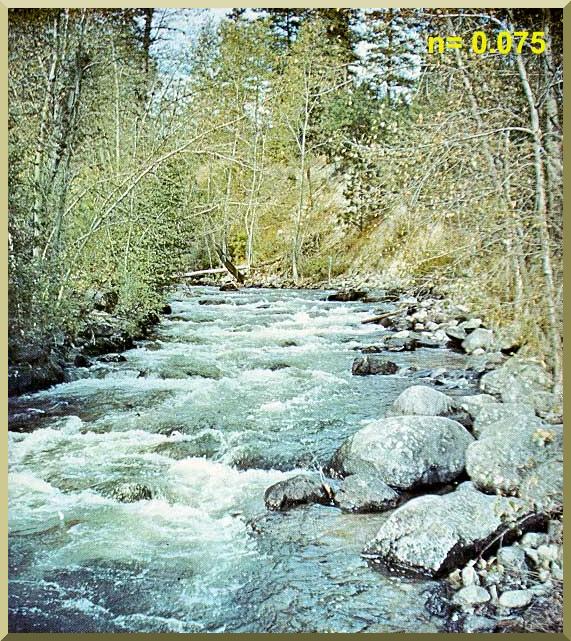

Barnes (1967) presented a full-color pictorial collection of fifty (50) typical stream channels across the United States, for which the Manning's n had been calculated by calibration.

The Barnes collection can be viewed online at Roughness Characteristics of Natural Channels.

The lowest value of Manning's n documented by Barnes is

The highest value of Manning's n is

|

|

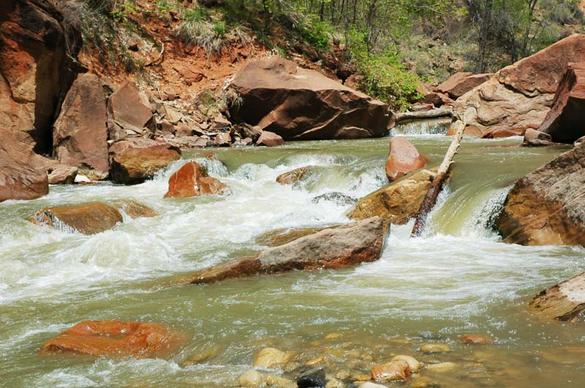

Arcement and Schneider (1989) presented a full-color pictorial collection of fifteen (15) typical flood plains in the Southestern United States, for which the Manning's n had been calculated by calibration.

The Arcement and Schneider collection can be viewed online at Manning's Roughness Coefficients for Natural Channels and Flood Plains.

The lowest value of Manning's n documented by Arcement and Schneider is

The highest value is

|

|

Factors affecting Manning's n

In practice, the value of Manning's n is highly variable.

In natural stream channels it can range from slightly lower than 0.020 for some very large rivers featuring a

relatively smooth boundary

The various factors affecting Manning's roughness coefficient are listed in Table 5-3.

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cowan (1956) has developed a rational methodology for estimating Manning's n. Cowan's equation is:

| n = (no + n1 + n2 + n3 + n4 ) m5 | (5-28) |

where:

no = basic n value for a straight, uniform, smooth channel

n1 = addition to account for surface irregularities

n2 = addition to account for variations in the size and shape of the cross section

n3 = addition to account for obstructions

n4 = addition to account for the effect of vegetation on flow conditions

m5 = factor to account for channel sinuosity (meandering).

Table 5-3 lists the appropriate values to be used in Eq. 5-28.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Table 5-4 lists values of Manning's n for channels of various kinds, compiled by Chow (1959).

For each kind of channel, the minimum, normal, and maximum values of n are shown.

The normal values are recommended only for channels with good maintenance.

Values generally recommended for design are shown in bold.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Click -here- to display the complete Table 5-4. |

5.5 COMPUTATION OF UNIFORM FLOW

|

|

From Eq. 5-2, the discharge in open-channel flow is:

| Q = V A = C R x S y A | (5-29) |

Equation 5-29 can be expressed as follows:

| Q = K S y = K S 1/2 | (5-30) |

in which K = conveyance, defined as:

| K = C R x A | (5-31) |

Or, alternatively:

| Q K = ______ S 1/2 | (5-32) |

Following Chézy:

| K = C A R 1/2 | (5-33) |

Following Manning, in SI units:

| 1 K = ____ A R 2/3 n | (5-34) |

In U.S. Customary units:

| 1.486 K = ________ A R 2/3 n | (5-35) |

The conveyance K contains information on friction and cross-sectional size and shape, and is independent of the channel slope.

Channels with composite roughness

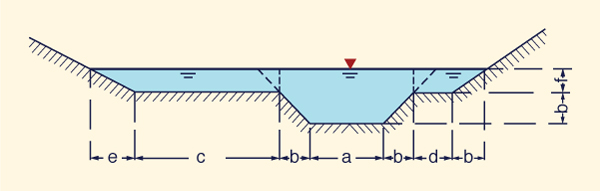

A channel that overflows its banks usually has more than one value of Manning's n, one for inbank flow, and two additional ones, one for left overbank and another for right overbank (Fig. 5-9).

A composite value of Manning's n may be calculated under the assumption that the velocities for all three subsections, inbank, left overbank, and right overbank, remain the same.

While this assumption is convenient, it sidesteps the issue of possible flow nonuniformity across the composite cross section.

Assume a channel of varying roughness along its wetted perimeter, with N being the number of subsections.

The wetted perimeters are: P1, P2, P3, ..., PN. The corresponding values of roughness are: n1, n2, n3, ..., nN. Assuming that all velocities are equal:

|

V1 = V2 = V3 = VN = V | (5-36) |

For any subsection

| 1 Vi = ____ Ri 2/3 S 1/2 ni | (5-37) |

| 1 Vi = ____ (Ai / Pi ) 2/3 S 1/2 ni | (5-38) |

The flow area for subsection i is:

|

Vi 3/2 ni 3/2 Pi Ai = _________________ S 3/4 | (5-39) |

The total flow area of the channel is:

|

V 3/2 n 3/2 P A = _________________ S 3/4 | (5-40) |

The total flow area is equal to the sum of the subareas. Therefore:

| V 3/2 n 3/2 P = ∑ (Vi 3/2 ni 3/2 Pi ) | (5-41) |

| N |

From Eq. 5-36, all the velocities are equal. Thus, Eq. 5-41 reduces to:

| n 3/2 P = ∑ (ni 3/2 Pi ) | (5-42) |

| N |

Thus, the value of Manning's n for a channel of composite cross section is:

| ∑ (ni 3/2 Pi ) N n = [ _________________ ] 2/3 P | (5-43) |

|

The cross section of a channel may be composed of several distinct subsections, and each of them may have a different roughness.

For example, an alluvial channel subject to seasonal flooding generally consists of a main channel and two side channels (Fig. 5-9).

The side channels are usually rougher than the main channel; therefore, the mean velocity in the main channel is usually greater than those of the side channels.

The Manning equation may be applied separately to each subsection, and the total discharge is equal to the sum of the subsection discharges.

For the channel as a whole, the mean velocity is equal to the total discharge divided by the total area.

The velocity distribution coefficient applicable to the whole channel is different from the velocity distribution coefficients applicable to each subsection.

The total velocity distribution coefficient may be computed as explained below.

Assume a total number of subsections N and several subsections i, where i varies from 1 to N. From continuity (Eq. 2-4):

| Qi = Vi Ai | (5-44) |

where Qi = discharge through subsection i, and Vi = mean velocity through subsection i, of flow area Ai. Furthermore, from Eq. 5-30:

| Qi = Ki S 1/2 | (5-45) |

where Ki = conveyance through subsection i (Eq. 5-33 or 5-34).

Combining Eqs. 5-44 and 5-45:

| Vi = (Ki / Ai) S 1/2 | (5-46) |

The total discharge is:

| N Q = ∑ Q i i = 1 | (5-47) |

Using Eq. 5-45 in Eq. 5-47:

| N Q = ( Σ Ki ) S 1/2 i = 1 | (5-48) |

From Eq. 2-4, Q = V A. Thus:

| N V = ( Σ Ki ) ( S 1/2 / A ) i = 1 | (5-49) |

From Eq. 2-24, the energy coefficient is restated as follows:

|

N Σ Vi 3 Ai i = 1 α = _____________ V 3A | (5-50) |

Likewise, from Eq. 2-31, the momentum coefficient is:

| N Σ Vi 2 Ai i = 1 β = _____________ V 2A | (5-51) |

Replacing Eqs. 5-46 and 5-49 into 5-50, the composite energy coefficient α, applicable to the entire cross section, is obtained:

N A2 [ Σ (αi Ki 3 / Ai 2 ) ] i = 1 α = ____________________________ N ( Σ Ki ) 3 i = 1 | (5-52) |

Likewise, replacing Eqs. 5-46 and 5-49 into 5-51, the composite value of β is:

N A [ Σ (βi Ki 2 / Ai ) ] i = 1 β = ____________________________ N ( Σ Ki ) 2 i = 1 | (5-53) |

Computation of uniform flow

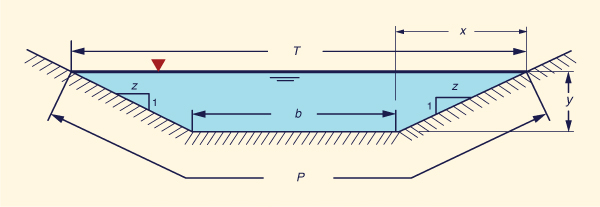

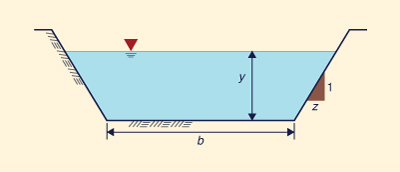

With reference to Fig. 5-10, the following proportion holds: z /1 = x /y. Then, the top width T is:

|

T = b + 2x = b + 2zy | (5-54) |

The flow area A is:

|

A = (b + x ) y = (b + zy ) y | (5-55) |

|

The wetted perimeter P is:

|

P = b + 2 (y 2 + z 2y 2 )1/2 | (5-56) |

Simplifying:

|

P = b + 2 y ( 1 + z 2 )1/2 | (5-57) |

From the Manning equation, the discharge Q is:

| k Q = _____ A R 2/3 S 1/2 n | (5-58) |

in which k = 1 in SI units, and k = 1.486 in U.S. Customary units.

Since R = A /P, Eq. 5-58 reduces to:

| Q n A 5/3 _________ = _______ k S 1/2 P 2/3 | (5-59) |

Replacing Eqs. 5-55 and 5-57 into Eq. 5-59:

| Q n [ (b + zy ) y ] 5/3 _________ = _____________________________ k S 1/2 [b + 2 y ( 1 + z 2 )1/2] 2/3 | (5-60) |

Simplifying:

| Q n Q n [ (b + zy ) y ] 5/2 - ( ________ ) 3/2 [ 2 y ( 1 + z 2 )1/2 ] - ( ________ ) 3/2 b = 0 k S 1/2 k S 1/2 | (5-61) |

The input data consisting of: (1) discharge Q, (2) bottom width b, (3) size slope z [z:H to 1:V, Fig. 5-10], (4) bottom slope S, and (5) Manning's n.

With given input data,

Eq. 5-61 is solved for the normal depth

Then, with Eqs. 5-54 and 5-55:

|

A D = ______ T | (5-62) |

|

Q V = ______ A | (5-63) |

Equation 5-61 is the general formula for uniform or normal flow, applicable to prismatic channels of trapezoidal cross section.

For a rectangular channel: z = 0. Likewise, for a triangular channel of symmetrical section: b = 0.

To solve Eq. 5-61, it is expressed in the following form:

| Q n Q n f (y) = [ (b + zy ) y ] 5/2 - ( ________ ) 3/2 [ 2 y ( 1 + z 2 )1/2 ] - ( ________ ) 3/2 b k S 1/2 k S 1/2 | (5-64) |

Making the change of variable x = y for simplicity:

| Q n Q n f (x) = [ (b + zx ) x ] 5/2 - ( ________ ) 3/2 [ 2 x ( 1 + z 2 )1/2 ] - ( ________ ) 3/2 b k S 1/2 k S 1/2 | (5-65) |

The solution of Eq. 5-65 is accomplished by a trial-and-error procedure.

An iterative algorithm based on function value is described below.

An example of normal flow is shown in Fig. 5-11.

Normal depth algorithm based on function value

|

|

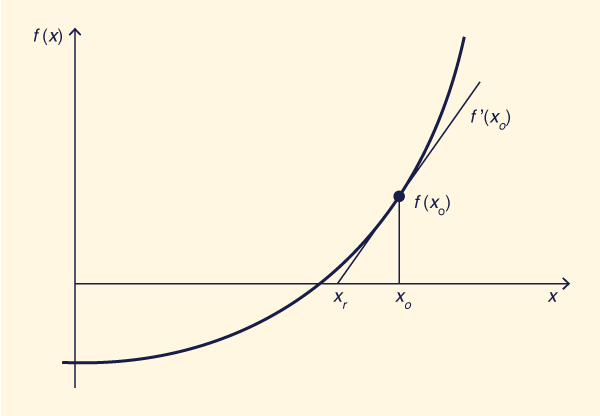

Newton's approximation to the root

The above iteration uses solely the value of the function to approximate to the root.

A faster algorithm makes use of Newton's approximation, which is based on the tangent.

Note that for Newton's iteration to work well, it is first necessary get close to the root using the function iteration described above.

Otherwise, Newton's tangent method may not converge.

With reference to Fig. 5-12, the value of the tangent at xo is:

|

f(xo) f '(xo) = _________ xo - xr | (5-66) |

where xo = current trial value of x, f(xo) = value of the function at xo, xr = new value of x, which gets closer to the root.

|

From Eq. 5-66, solving for xr :

|

f (xo) xr = xo - ________ f '(xo) | (5-67) |

As shown in Fig. 5-12, when f (xo) increases with xo (as is the case for Eq. 5-65), as the root is passed, the function value and the tangent value are positive; therefore, the denominator of Eq. 5-66 is also positive, and xr lies to the left of xo.

With each subsequent iteration, the root is approximated in a sawtooth fashion, until the specified tolerance is satisfied.

It is readily shown that Eq. 5-67 applies also when f (xo) decreases as xo increases, i.e., as in the case of critical flow, see Section 4.2.

The value of f '(x) is:

|

Q n f ' (x) = x 5/2 (5/2) (b + zx ) 3/2 z + (b + zx ) 5/2 (5/2) x 3/2 - ( ________ ) 3/2 [ 2 ( 1 + z 2 )1/2 ] k S 1/2 |

| (5-68) |

Simplifying Eq. 5-68:

|

Q n f ' (x) = 5 z x 5/2 (b + zx ) 3/2 + 5 x 3/2 (b + zx ) 5/2 - ( ________ ) 3/2 ( 1 + z 2 )1/2 k S 1/2 | (5-69) |

The procedure for Newton's approximation to the root of Eq. 5-65 is described below.

Normal depth algorithm: Newton's approximation

|

Example 5-1.

Using ONLINE CHANNEL 01,

calculate the critical flow depth for the

following flow conditions: Q = 3 m3/s;

ONLINE CALCULATION. Using the

ONLINE CHANNEL 01 calculator,

the normal depth is |

Example 5-2.

Using ONLINE CHANNEL 01,

calculate the critical flow depth for the

following flow conditions: Q = 20 ft3/s;

ONLINE CALCULATION. Using the

ONLINE CHANNEL 01 calculator,

the normal depth is |

5.6 COMPUTATION OF FLOOD DISCHARGE

|

|

The high stages and swift currents that prevail during floods combine to increase the risk of accident and bodily harm (Fig. 5-13).

Therefore, it is generally not possible to measure discharge during the passage of a flood.

An estimate of peak discharge can be obtained indirectly by the use of open channel flow formulas.

This is the basis of the slope-area method.

|

To apply the slope-area method for a given river reach, the following data are required:

The reach length,

The fall, i.e., the mean change in water surface elevation through the reach,

The flow area, wetted perimeter, and velocity head coefficients at upstream and downstream cross sections, and

The average value of Manning's n for the reach.

The following guidelines are used in selecting a suitable reach:

- High-water marks should be readily recognizable (Fig. 5-14).

The reach should be sufficiently long so that fall can be measured accurately.

The cross-sectional shape and channel dimensions should be relatively constant.

The reach should be relatively straight, although a contracting reach is preferred over an expanding reach.

Bridges, channel bends, waterfalls, and other features causing flow nonuniformity should be avoided.

|

The accuracy of the slope-area method improves as the reach length increases (Fig. 5-15).

A suitable reach should satisfy one or more of the following criteria:

The ratio of reach length to hydraulic depth should be greater than 75,

The fall should be greater than or equal to 0.15 m: F ≥ 0.15 m, and

The fall should be greater than either of the velocity heads computed at the upstream and downstream cross sections.

|

The procedure consists of the following steps:

Calculate the conveyance K at upstream and downstream sections:

1

K1 = ( __ ) A1 R1 2/3

n

(5-70a) 1

K2 = ( __ ) A2 R2 2/3

n

(5-70b) in which K = conveyance; A = flow area; R = hydraulic radius; n = average reach Manning's n; and 1 and 2 denote the upstream and downstream sections, respectively (Eq. 5-70 is in SI units).

Calculate the reach conveyance, equal to the geometric mean of upstream and downstream conveyances:

K = ( K1 K2 )1/2 (5-71) in which K = reach conveyance.

Calculate the first approximation to the energy slope:

F

S = ___

L

(5-72) in which S = first approximation to the energy slope; F = fall; and L = reach length.

Calculate the first approximation to the peak discharge:

Qi = K S 1/2 (5-73) in which Qi = first approximation to the peak discharge.

Calculate the velocity heads:

α1 ( Qi /A1 ) 2

hv1 = ______________

2g

(5-74a) α2 ( Qi /A2 ) 2

hv2 = ______________

2g

(5-74b) in which hv1 and hv2 = velocity heads at upstream and downtream sections, respectively; α1 and α2 = velocity head coefficients at upstream and downstream cross sections, respectively; and

g = gravitational acceleration.Calculate an updated value of energy slope:

F + k ( hv1 - hv2 )

Si = ___________________

L

(5-75) in which Si = updated value of energy slope, and k = loss coefficient. For expanding flow, i.e.,

A2 > A1, k = 0.5; for contracting flow , i.e.,A1 > A2, k = 1. Calculate an updated value of peak discharge:

Qi = K Si 1/2 (5-76) -

Return to step 5 and repeat steps 5 to 7. The procedure is terminated when the difference between two successive values of peak discharge Q obtained in step 7 is negligible. In practice, this is usually accomplished within three iterations.

5.7 UNIFORM SURFACE FLOW

|

|

Overland flow over a catchment surface is referred to as surface flow.

Typically, in overland flow, the depth of flow is very small compared to the width.

Under these conditions, the flow may be either laminar or turbulent, depending on the absolute and relative roughnesses.

If velocities and depths of flow are sufficiently small, the flow may be laminar; otherwise, the flow may be transitional or turbulent, depending on the Reynolds number (Section 1.4).

In overland flow, a mixed laminar-turbulent regime is commonly present.

This type of flow is characterized by changes from laminar to turbulent regime under the spatially varying flow conditions normally encountered in catchment/watershed/basin surface flow.

Under laminar flow conditions, the exponent of the rating for surface flow is β = 3.

Under turbulent flow conditions, the exponent is

Mixed laminar-turbulent flow regimes feature values of β varying between laminar and turbulent.

Laminar surface flow

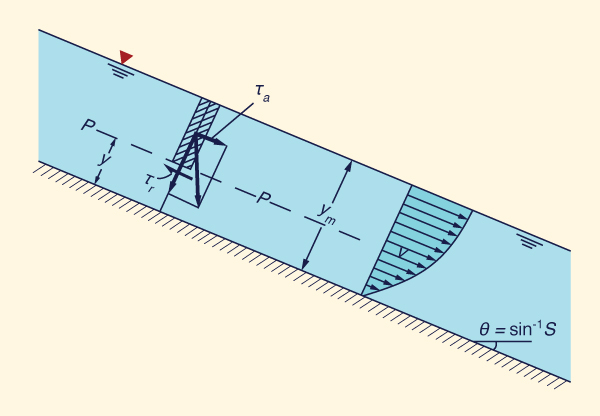

With reference to Fig. 5-16, the acting shear stress at level P is:

| τa = γ (ym - y ) S | (5-77) |

According to Newton's law of viscosity, the resisting shear stress at P is proportional to the vertical velocity gradient:

|

dv τr = μ _____ dy | (5-78) |

in which μ = a constant of proportionality referred to as the dynamic viscosity.

|

Equating acting and resisting stresses:

|

dv μ _____ = γ (ym - y ) S dy | (5-79) |

In differential form:

|

μ dv = γ (ym - y ) S dy | (5-80) |

The mass density γ = ρg, and the dynamic viscosity μ = ρν, in which ν = kinematic viscosity. Thus, Eq. 5-80 reduces to:

| gS dv = _____ (ym - y ) dy ν | (5-81) |

Integrating Eq. 5-81:

| gS v = ∫ _____ (ym - y ) dy ν | (5-82) |

| gS y 2 v = _____ [ ym y - _____ ] + C ν 2 | (5-83) |

where C is a constant of integration. For v = 0: y = 0; therefore: C = 0, and the mean velocity-flow depth relation is:

| gS y 2 v = _____ [ ym y - _____ ] ν 2 | (5-84) |

Equation 5-84 reveals that the velocity profile of uniform surface flow has a parabolic distribution.

The discharge-depth rating is obtained by integrating Eq. 5-84 between the limits of 0 and ym, i.e., from bottom to surface, to yield:

| gS y 2 q = ∫ v dy = _____ ∫ [ ym y - _____ ] dy ν 2 | (5-85) |

| gS ym 2 ym 3 q = _____ [ _____ - _____ ] ν 2 6 | (5-86) |

which reduces to:

| gS q = ______ ym 3 3ν | (5-87) |

Or:

|

q = CL ym 3 | (5-88) |

where CL = laminar discharge rating coefficient, defined as:

| gS CL = ______ 3ν | (5-89) |

Note that under laminar flow, the exponent of the discharge rating is β = 3 (Eq. 5-88), and the rating is a function of the internal friction, or internal viscosity, represented by the kinematic viscosity ν.

Thus, laminar flow is a function of temperature.

Given Eq. 5-77, the mean velocity in laminar flow, v = q /ym, is:

|

v = CL ym 2 | (5-90) |

The turbulent Chézy discharge rating is:

|

q = C S 1/2 ym 3/2 | (5-91) |

The turbulent Manning discharge rating in SI units is:

|

q = (1/n) S 1/2 ym 5/3 | (5-92) |

Likewise, in U.S. Customary units is:

|

q = (1.486 / n) S 1/2 ym 5/3 | (5-93) |

It is seen that the exponent of the rating varies from β = 3 for laminar flow (Eq. 5-88), to β = 3/2 for turbulent Chézy friction (Eq. 5-91), or β = 5/3 for turbulent Manning friction (Eq. 5-92).

In uniform surface flow, values of β in the range between laminar and turbulent represent the condition of mixed laminar-turbulent flow (Section 1.3).

The Vedernikov number is:

| (β - 1) v V = ____________ (g y )1/2 | (5-94) |

Under V = 1, the flow is neutrally stable, promoting the development of roll waves (Fig. 5-17).

The relation between the exponent β and the Vedernikov number

Relation between exponent β and Vedernikov number

|

|

QUESTIONS

|

|

When does uniform flow become unstable?

What is the Chezy formula based on?

What is the difference between the Manning and Chezy formulas?

What is the minimum value of Manning's n that can be achieved in practice?

What is the range of values of Manning's n measured by Barnes?

What is the range of values of Manning's n measured by Arcement and Schneider for flood plains?

Why is the calculation of composite roughness using Eq. 5-43 only an approximation?

What five input variables are used in the computation of uniform flow in a trapezoidal channel?

Why is it better to use Newton's approximation to the root rather than relying solely on the function approximation to solve the normal depth problem?

What is the minimum ratio of reach length to hydraulic depth in the slope-area method?

What is the exponent of the discharge-depth rating under laminar flow conditions?

What is the exponent of the discharge-depth rating under turbulent Chezy friction in hydraulically wide channels?

What is the exponent of the discharge-depth rating under turbulent Manning friction in hydraulically wide channels?

Under what value of Froude number is the flow likely to become unstable under laminar flow conditions?

PROBLEMS

|

|

Prove that the Darcy-Weisbach friction factor is related to Manning's n by the following relation:

fD = 8 g n 2 / (k 2 R 1/3)

in which fD = Darcy-Weisbach friction factor, g = gravitational acceleration, R = hydraulic radius, and k = constant specific for the system of units, equal to 1 in SI units and 1.486 in U.S. Customary Units. Express the relation in SI and U.S. Customary units.

Calculate the discharge Q using the Manning equation, given: flow area A = 23.5 ft2; hydraulic radius R = 5.6 ft; channel slope S = 0.0025; Manning's n = 0.035.

Calculate the discharge Q using the Manning equation, given: flow area A = 45 m2; hydraulic radius R = 6 m; channel slope S = 0.003; Manning's n = 0.04.

Given f = 0.0025, calculate the discharge Q for a flow area A = 12.4 m2, hydraulic radius

R = 2.1 m; and channel slope S = 0.0015.Given f = 0.0035, calculate the discharge Q for a flow area A = 18 ft2, hydraulic radius R = 4.5 ft; and channel slope S = 0.0018.

Use ONLINE CHANNEL 01 to calculate normal depth, velocity, and Froude number for the following case: Q = 150 m3/s, b = 10 m, z = 2, So = 0.0005, n = 0.025.

Use ONLINE CHANNEL 01 to calculate normal depth, velocity, and Froude number for the following case: Q = 250 cfs, b = 20 ft, z = 1, So = 0.001, n = 0.030.

Using ONLINE CHANNEL 15, calculate the discharge for a prismatic channel with b = 20 ft,

y = 3 ft, z = 2, n = 0.025, S = 0.0016.

Fig. 5-18 Definition sketch for a trapezoidal channel.

Using ONLINE CHANNEL 15, calculate the discharge for a prismatic channel with b = 6 m,

y = 1 m, z = 1.5, n = 0.015, S = 0.0002.A recent flood on Clearwater Creek has left observable water marks on a certain river reach. To estimate the flood magnitude, hydraulic data has been measured at two cross sections A and B, a distance of 1,850 ft apart. The reach fall between the cross sections is 9.1 ft and the average Manning's n is 0.035. The upstream flow area, wetted perimeter, and Coriolis α coefficient are 550 ft2, 55 ft, and 1.17; the downstream flow area, wetted perimeter, and α coefficient are 620 ft2, 52 ft, and 1.10. Use SLOPE AREA to calculate the flood discharge.

Calculate the unit-width discharge in an overland flow plane, under laminar flow, with mean depth of 1.5 cm and slope of 0.001. Assume water temperature T = 20oC. Report discharge in L/s/m.

REFERENCES

|

|

Arcement, G. J. and V. R. Schneider. 1989. Guide for selecting Manning's roughness coefficients for natural channels and flood plains. U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 2339, Washington, D.C.

Barnes, H. A. 1967. Roughness characteristics of natural channels. U.S. Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 1849, Washington, D.C.

Cowan, W. L. 1956. Estimating hydraulic roughness coefficients. Agricultural Engineering, Vol. 37, No. 7, pp. 473-475, July.

Chow, V. T. 1959. Open-channel hydraulics. McGraw-Hill, New York.

Henderson, M. H. 1966. Open-channel flow. Macmillan, New York.

Simons, D. B., and E. V. Richardson. 1966. Resistance to flow in alluvial channels. U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper 422-J, Washington, D.C.

Williamson, J. 1951. The laws of flow in rough pipes. La Houille Blanche, Vol. 6, No. 5, September-October, p. 738.

| http://openchannelhydraulics.sdsu.edu |

|

150710 10:30 |